Need finding, tasks and storyboards in HCI

Need finding is a fundamental activity in user interface design, because it allows us to understand our users and their needs. With this post we see how to conduct it, and what it consists of.

As the name implies, need finding is the Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) activity aimed at knowing the needs of the user.

Need finding is fundamental because it allows us to identify exactly:

- User’s problems;

- Their frustrations;

- Their way of doing;

- Needs;

- Goals.

Need finding then allows us to think about and to design a product tuned to the needs of those who will use it.

There are several methods (also called query techniques) to acquire information about user needs, including interviews and questionnaires. Before looking at them, it is important to fix in mind that during need finding:

- We must be open to unanticipated findings;

- We need to consider the context: the environment in which we conduct the need finding, the type of user, their abilities, etc;

- We must note differences and similarities between people;

- We must not introduce bias in the tests;

- We need to pay attention to the user’s perception.

Before moving on, let’s pause with this sentence that the prof. said:

Early solutions limit the chances of understanding the problem and its possible solutions.

Query techniques: how to do need finding.

We have five ways of gathering information:

Interviews

We take a target person and conduct a short interview aimed at understanding their needs. Some interviewer prefer to prepare a set list of questions, while others prefer a list of topics, to be modulated according to the character of the person in front of us and how the interview proceeds.

Either way, it is important to be prepared to avoid wasting people’s (and our) time.

There are questions-or rather, formulations of questions-that should be avoided, because they can give us wrong information, inaccurate, exaggerated, or otherwise unhelpful. These concern:

- Hypothetical scenarios: people tend to approach these questions in an aspirational way, that is, answering in the way they believe is expected of them. Instead, we should first understand what is the user’s way of doing things, their habits, and how they have dealt with some similar problems.

- Questions that contain an answer: “so you haven’t had any problems with x?”. It is easy to make this mistake at certain times of laddering (which we will see in a moment). It is best to avoid giving people half-suggestions that they are sure to cling to.

- Questions that are too general: if not thoroughly investigated, they turn out to be a waste of time.

- Questions with obvious answers: tolerable only to warm up shy people, to find out if the respondent is distracted, crazy, or fooling us.

- Request for design advice or suggestions: what are we doing taking an HCI class if we’re just going to have some random guy in the middle of the street design the app?

- Frequency of events: “How many times do you eat pizza in a week?”. The problem with these questions is that they require people to make a fairly complicated estimate, in their heads and without preparation. I don’t know how to answer such a question, unless I ate pizza exactly n times a week. Otherwise, I would have to estimate a frequency based on what I remember. Instead, it is better to ask, “Do you remember the last time you had pizza?” and the answer already gives us a better frame.

Notable users

We have three categories of users who can give us useful information during need finding:

- Lead users:

- Early adopters.

- Autonomous.

- Fairly knowledgeable.

- They benefit from innovations.

- They bring up new needs.

- Extreme users

- They heavyly use services (e.g., for work).

- They have amplified needs.

- They are also competent and autonomous.

- Domain experts:

- They have abstract knowledge.

- They have useful aggregate data.

- They have some useful studies.

Before moving on, pull out a couple of examples for the first two categories. Question: if I use IFTTT and have at least one applet that links my email to something, can I say I am an extreme email user?

Ways of conducting interviews.

We have five cumulative and customizable techniques: with a minimum expenditure of €99

- Laddering: delving into depth, such as asking “why?” over and over again;

- Cultural context: questions aimed at understanding the context;

- Intercepts: one dry question;

- Process mapping: getting a process described;

- History: understanding behavior by having sequences of events described.

Summing up:

- There are some questions to avoid.

- There are 3 notable users.

- There are 5 techniques for conducting interviews.

- Extras: of course we need to take notes.

- Extra: better if there are two of us: one talks, the other writes.

- Extras: we can record audio, if we have their permission.

- Bonus: if this person is very interested in the project, maybe we get an email address to contact them again in the future.

Questionnaires

Unlike interviews, questionnaires are analysis-oriented and give us more data in less time. The considerations regarding wording to avoid also apply to questionnaires.

Questionnaires can either be on paper or electronic, and there are several services to create them (e.g., Google Forms). In a good questionnaire we should:

Avoid grammatical errors: trivial, I know.

Use appropriate language: understand your target and know when to be formal and when to chill out.

Forcing the user to unbalance: for example, setting an even number of answers to multiple-choice questions so that the user cannot select the neutral answer.

Prevent the user from making inconsistent choices: how many times have we seen questions done this way?

What messaging apps do you use?

- WhatsApp;

- Telegram;

- Slack;

- None of these.

What happens if I select also the last option?

What messaging apps do you use?

- WhatsApp;

- Telegram;

- Slack;

- None of these.

The point here is about using controls/widgets that are appropriate to the question (radio buttons, checkboxes, free response, scale, etc.).

Use conditional logic: suppose we want to display a different set of questions, depending on the messaging app the user uses. Questionnaire creation services generally allow you to create stuff like (but also more complex than):

- If the user answers Yes –> send it to the X section.

- If they answers No –> finish.

This also allows you to reinforce the previous point.

How do we tell if the questionnaire is working and well written? Pilot test: we observe a person as they answer the questionnaire, and make note of misunderstandings, problems, or generally things that can be improved; after each test we fix the questionnaire. 3-5 people are sufficient.

Summing up:

- Questionnaires give us quantitative data;

- We should plan them wisely.

- They require a pilot test.

Diaries

This query technique involves collecting information for extended periods of time.

Camera studies

Here we video record users in context, and try to understand their needs from behaviors.

Pager studies

Precise questions at a specific time (e.g., rating the quality of the video call).

Tasks and Storyboards

From the need finding we produce a list of needs. Of these needs we extract the most interesting ones, from which we derive tasks.

For example in a messaging app, some tasks may be:

- Creating a new chat;

- Creating a new group;

- Sending an attachment.

For each task we are interested in a scenario, namely:

- Underlying problem and action to be taken;

- Context;

- Users and roles involved;

- Role of the interface;

- Context after task execution.

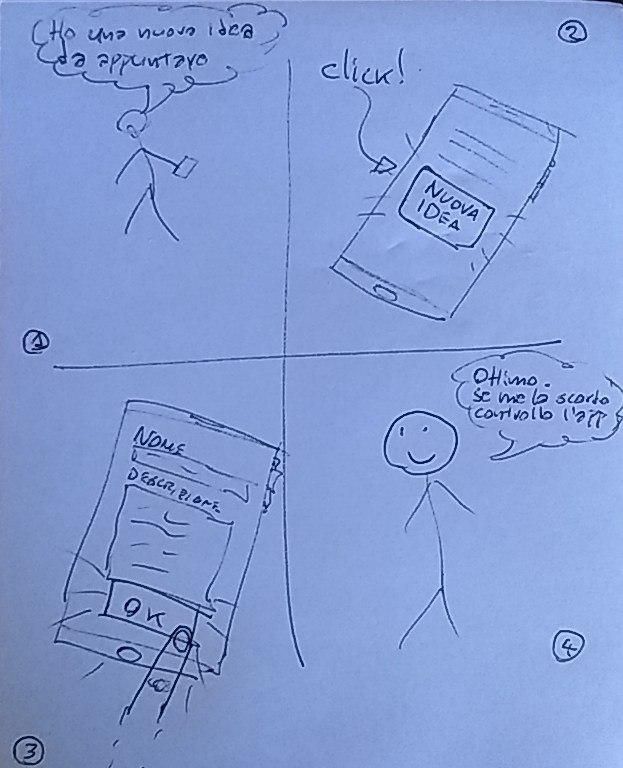

We can graphically represent this information with a storyboard, that is, a silly little drawing that describes the general idea of the task.

The storyboards must be:

- Drawn on paper.

- Freehand.

- Quick.

- Easy to read.

- Poor in text.

- Without UI.

Why? Because we don’t want to waste our time.

In conclusion.

In this post we have seen that need finding exists, and we know why it is important. We saw some techniques for doing it, and delved into interviews and questionnaires. Then we saw that from need analysis we can find tasks, which flow into storyboards.